The famine came to Ireland in 1845, and by 1846, death gripped the land. Eventually, over a million would die, and as many as two million would emigrate in search of salvation. Those starving were forced into desperate acts to stay alive, and crime increased dramatically, much of it petty crime of food and low-value goods. Many who were convicted of a crime were sentenced to transportation overseas, which served the dual purpose of populating the colonies and ridding Ireland of its unwanted. But foreign colonies like Australia were beginning to refuse to take convicts, complaining of the quality of the convicts being sent. The prison authorities were overwhelmed by spiralling numbers, and locations were urgently scouted to hold the ballooning convict population.

The famine came to Ireland in 1845, and by 1846, death gripped the land. Eventually, over a million would die, and as many as two million would emigrate in search of salvation. Those starving were forced into desperate acts to stay alive, and crime increased dramatically, much of it petty crime of food and low-value goods. Many who were convicted of a crime were sentenced to transportation overseas, which served the dual purpose of populating the colonies and ridding Ireland of its unwanted. But foreign colonies like Australia were beginning to refuse to take convicts, complaining of the quality of the convicts being sent. The prison authorities were overwhelmed by spiralling numbers, and locations were urgently scouted to hold the ballooning convict population.

Spike Island continued its role as a home to the British military after the British-French wars ended with the defeat of Napoleon. But the fort was incomplete at this point, its necessity for defence was diminished and it was soon eyed up by the prison authorities as a potential solution to their problem of overcrowding. This arrangement suited the military as the free labour could be put to use finishing off incomplete areas of the fort. Advances were made and on 9th October 1847, the first prisoners in two centuries were held on Spike Island, when 109 men were transferred to its hastily converted accommodation blocks. It was anticipated the island would hold 800 prisoners but within a few short years, the numbers swelled to over 2300, making it the largest known prison in the world. Prisoners were even sent from the UK to fill its cells and it held over half the prisoner population of Ireland.

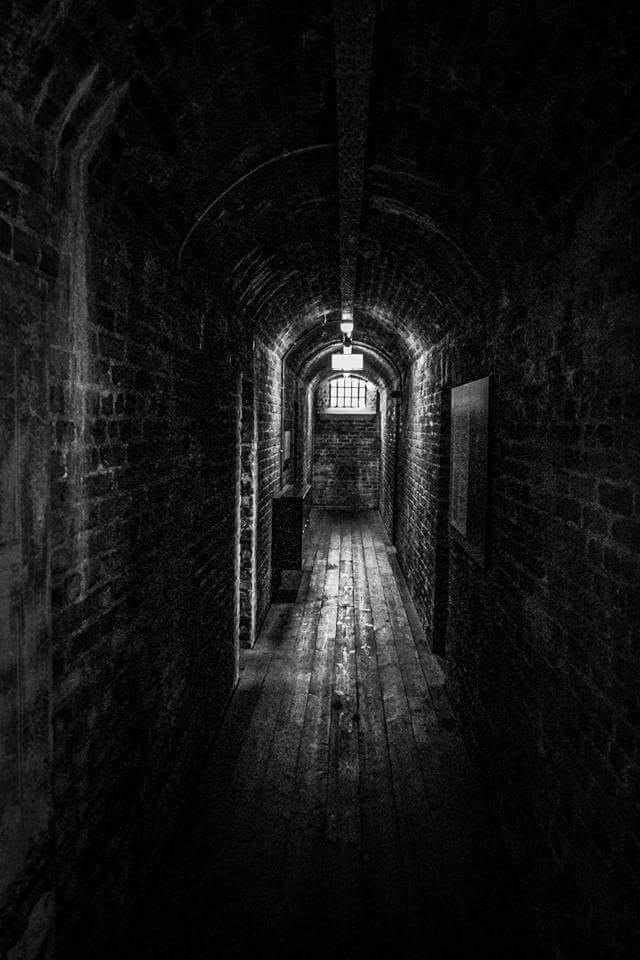

No women were held on the island but men and boys as young as 12. An especially converted ‘children’s prison’ held up to 100 boys in a former ammunition storehouse, the youngsters sleeping in hammocks suspended from chains in the roof. The conditions for the men were horrific and overcrowding was a serious issue. New blocks were brought online like a timber prison and an iron prison but these also quickly were filled to more than double their capacity. As a result, the death rate was extortionate at over 10% of prisoners and as many as 1000 would die in the care of the prison service in the first 6 years of its existence. In its 36-year existence from 1847 – 1883 over 1300 would perish and as many as 750 died under the watch of the first surgeon on the island, who was said to be drunk and opiate. Today two mass graves on the island attest to the awful conditions. For those who were unruly in prison, the treatment was even worse as they were sent to solitary confinement in the ‘dark cells’. These were initially converted toilets at the end of the deep tunnels under the fort’s walls at Bastion 3, but eventually, in 1858 a purpose-built ‘punishment block’ was started after a warder was murdered. Men held here would be chained to the wall by their neck and legs for up to 23 and a half hours a day, in windowless, furniture less cells. They slept on straws on the ground in appalling conditions. The cell block broke many men and its name was cursed across Ireland.

No women were held on the island but men and boys as young as 12. An especially converted ‘children’s prison’ held up to 100 boys in a former ammunition storehouse, the youngsters sleeping in hammocks suspended from chains in the roof. The conditions for the men were horrific and overcrowding was a serious issue. New blocks were brought online like a timber prison and an iron prison but these also quickly were filled to more than double their capacity. As a result, the death rate was extortionate at over 10% of prisoners and as many as 1000 would die in the care of the prison service in the first 6 years of its existence. In its 36-year existence from 1847 – 1883 over 1300 would perish and as many as 750 died under the watch of the first surgeon on the island, who was said to be drunk and opiate. Today two mass graves on the island attest to the awful conditions. For those who were unruly in prison, the treatment was even worse as they were sent to solitary confinement in the ‘dark cells’. These were initially converted toilets at the end of the deep tunnels under the fort’s walls at Bastion 3, but eventually, in 1858 a purpose-built ‘punishment block’ was started after a warder was murdered. Men held here would be chained to the wall by their neck and legs for up to 23 and a half hours a day, in windowless, furniture less cells. They slept on straws on the ground in appalling conditions. The cell block broke many men and its name was cursed across Ireland.

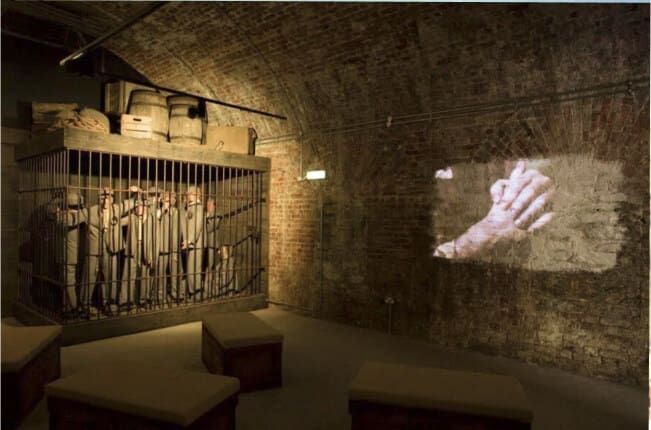

Eventually, as the famine eased so did the prisoner population and by the end of the 1850’s there were around a thousand prisoners held. They were involved in improvement works to the fort and even deployed to their forts in the harbour and to the nearby naval base Haulbowline via a bridge/causeway constructed to move men and materials. By this period transportation was largely ended and men were finishing their terms in Irish gaols. The numbers whittled down until eventually the prison was closed in 1883 and so ended a dark chapter in the history of Spike Island. Visitors today can explore the Punishment block which is incredibly intact and restored, including its chilling ‘dark cells’. The former children’s prison is now an exhibition space on crime and punishment and both areas give an amazing sense of what life was like for convicts almost 200 years ago while telling the stories of some of Ireland’s most interesting convict characters.

Eventually, as the famine eased so did the prisoner population and by the end of the 1850’s there were around a thousand prisoners held. They were involved in improvement works to the fort and even deployed to their forts in the harbour and to the nearby naval base Haulbowline via a bridge/causeway constructed to move men and materials. By this period transportation was largely ended and men were finishing their terms in Irish gaols. The numbers whittled down until eventually the prison was closed in 1883 and so ended a dark chapter in the history of Spike Island. Visitors today can explore the Punishment block which is incredibly intact and restored, including its chilling ‘dark cells’. The former children’s prison is now an exhibition space on crime and punishment and both areas give an amazing sense of what life was like for convicts almost 200 years ago while telling the stories of some of Ireland’s most interesting convict characters.