John Patrick Leonard

An influential Spike Islander in Paris

On the 12th of October, 1814, John Patrick Leonard was born on Spike Island, the result of his father’s employment as an engineer working on nearby Haulbowline Island. His father passed away when John Leonard was just four and he was raised by his uncle P.J Leonard, an Irish Christian Brother who founded schools in Cork. As a teenager the young John was sent to school in France, at Boulogne-Sur-Mer, and so began a lifelong love affair with France. He was back and forth between the nations until he settled in Paris in 1834, first studying medicine at which he failed miserably. He moved into studying English language and literature and became a teacher, at which he fared little better if the 1844 inspectors report from his school in Sens is to be believed. He was described as having an;

“Offhand manner. Mr Leonard is a feckless man and lover of disorderly pleasures. Inconsistent and prodigious with his money, he is not held in much esteem. Often, pupils that are docile with other teachers show him no respect and partake in acts of indiscipline in his presence. This teacher lacks authority and leadership”.

Clearly, if John Patrick Leonard was going to make a positive impression on his country of choice, it would not be in the field of academia.

A friend to Fenians and revolutionaries

Fortunately for Irish interests, his passions and talents lay elsewhere. Despite his modest station, Leonard was extremely skilled at networking among France’s elite, and he curried favour with some of the leading lights of French society. Foremost among his friends were Marshall Patrice MacMahon and Adolphe Thiers, both future Presidents of France. He counted the Bishop of Orleans as a close friend, and no doubt a useful ally.

Maximizing these connections, Leonard was endlessly generous with his time in the advancement of Irish Nationalism. He became known as the unofficial Irish Ambassador for the remaining decades of his life. He petitioned the French government to intervene in the deportation of the leaders of Ireland’s 1848 rebellion and welcomed many of them to France. Men like John Mitchel, who he befriended and accompanied to present an Irish sword to the French President in 1860. He stood in for Mitchel at his daughter’s funeral, as the exiled nationalist had returned to America when she died. John Patrick Leonard became aqquainted with the aging United Irish exiles, like William Corbet and William Smith O’Brien, just as readily with the new breed of Young Irelanders – Charles Gavin Duffy, John O’Leary, John Devoy and James Stephens, a whos who of 19th century Irish rebellion.

Paris had become something of a university of revolution for Irish nationalists, some of them exiled from Ireland. Here they could converse freely without looking over their shoulders, not something they could do back in Ireland. The Emperor Napoleon III considered their presence useful, something of a bargaining chip with the British, so the Irish were viewed with a mixture of fascination and trepidation. John Patrick Leonard became the focal point of these rebels, Irish nationalists visiting France like Thomas Francis Meagher, who Leonard brought to the cafes and restaurants of Paris, facilitating meetings.

It was with Meagher and another nationalist, William Smith O’Brien, that Leonard made arguably his enduring contribution to the Irish cause. Meagher was in France to study the learning’s of their revolutions, and Leonard was entertaining the visitors. He took the trio to the theatre to see ‘Phedre’, a French tragedy involving the lead actress singing a stirring version of the Marseillaise, while waving the French tri-colour. Meagher was said to be most moved, and saw the value of the symbolism. Prior to returning to Ireland, Meagher was presented with a green, white and gold tri-colour, woven by a group of sympathetic French women at the behest of Leonard, taking the French flag as it guide. It was this tri-colour that the returning Thomas Francis Meagher waved over the Mall in Waterford in 1848, in what was the first ever public outing of what would become the Irish national flag. Meagher would tell those present;

‘The white in the centre signifies a lasting truce between Orange and Green. I trust that beneath its folds the hands of the Irish Catholic and the Irish Protestant may be claspied in generous brotherhood’.

It is not recorded who exactly decided the choice of green, white and gold, but it is difficult to imagine Leonard being far removed from the decision making. With respect to the French ladies who forever since have been reported as crafting the flag, the work was completed at Leonard’s behest and it is decidedly unlikely they came up with the design. Tri-colours of various arrangements had been recorded in Ireland as early as 1830 when they were used in cockades and rosettes – knotted ribbons and pinned badges. The use of the colours and the deep symbolism of the green, white and gold suggest a deeper Irish understanding. It is possible it was solely Meagher’s, O’Brien’s or Leonard’s design, but the more likely situation is it was the three men who came to the design in unison, arguing the various points following their trip to the theatre prior to having it locally fashioned.

There is no questioning it was Leonard that directed the first flags fabrication, and the ceremonial nature of its presentation. As he had for decades before and after, John Patrick Leonard was pulling unseen strings, waging his own soft war, and representing on behalf of the Irish nation.

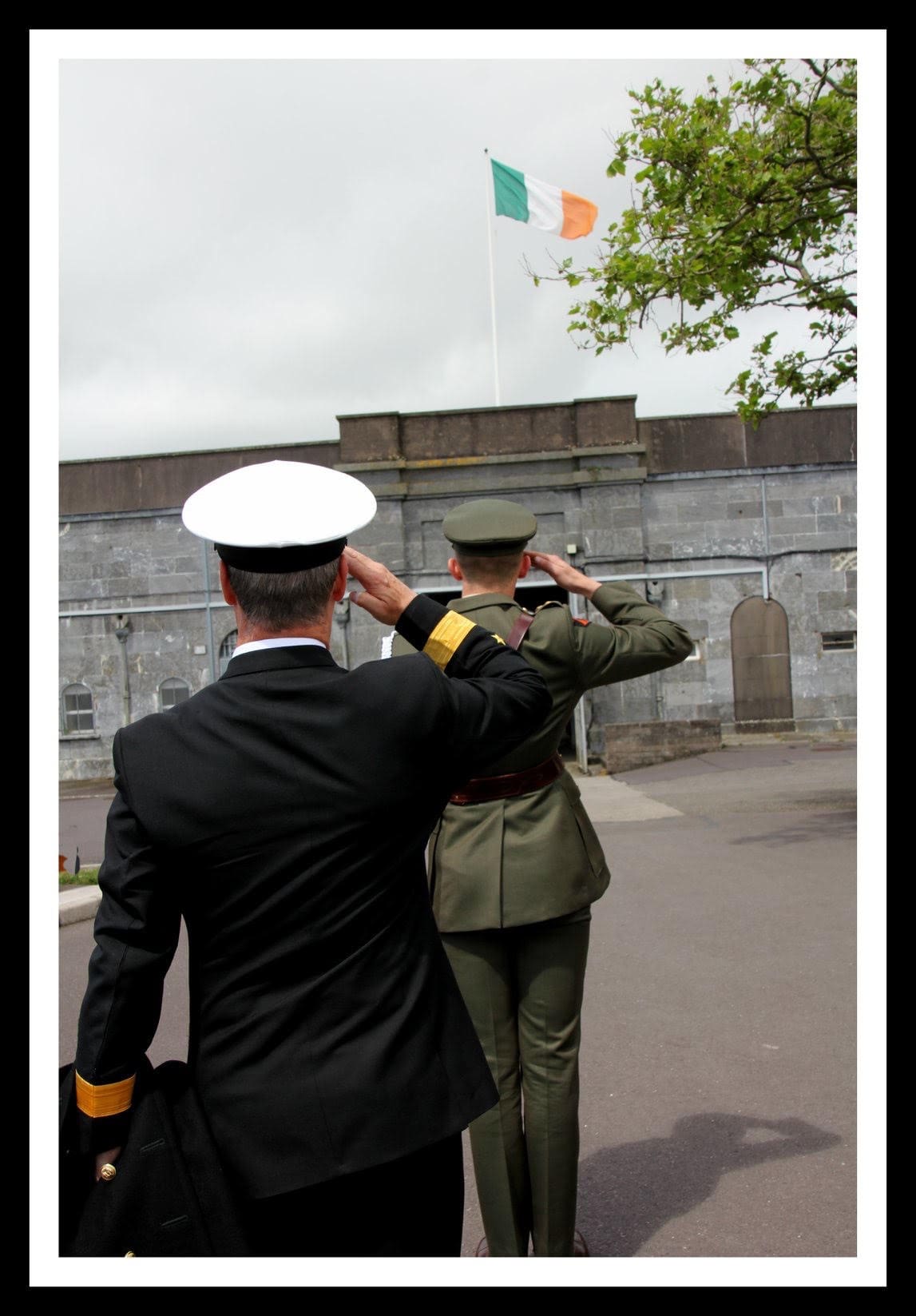

He is remembered on Spike Island as an ex-resident who did much for the Irish cause.